|

| A drone |

By Duke Tagoe

A “drone” has attacked and caused severe injuries to

28 years old Issah Salifu, a bartender at the Asabea Spot at Kokomlemle in

Accra.

The accident occurred Sunday afternoon on the Hearts

Lane adjacent the Old Press Centre in what eyewitnesses described as a

frightening incident.

According to Issah, he was walking on the Hearts Lane

when he was struck heavily at the back by what he called a “small helicopter”.

He fell to the ground and swellings started forming around his face and the

limbs.

Issah was immediately rushed to the Cocoa Clinic at

Kaneshie but was later referred to the Korle Bu Teaching hospital where doctors

subjected him to bouts of injections and a prescription of what he described as

expensive medicines.

The owner of the drone whose name has only been given

as ‘Sam’ is alleged to have told neighbors around the Hearts Lane, that he is a

staff of the Brazilian construction company Queiroz Galvao currently

constructing the magnificent overpass at the Kwame Nkrumah Circle.

According to ‘Sam’ he was mandated by the company to

put the drone in flight to take pictures of the overpass at a certain distance

in the sky, but lost control of the drone a few minutes after it went into

flight.

Doctors also prescribed Naklofen duo 75 mg, Salicyclic

Acid Ointment and Rubaxin Tablets for Issah.

Naklofen is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

with analgesic and antipyretic action. It is used for the treatment of all

rheumatic diseases and for the alleviation of different types of pain and other

pain syndromes in injuries and after other surgical procedures in the kidneys.

“Sometimes when I wake up in the morning I feel a very

sharp pain in the area around my backbone and I have difficulties standing for

long hours. I hope that my pain will go away after I complete my medication”

Issah told this reporter.

A drone is a small aircraft piloted by computers on

board or by remote controls on the ground. They are often used for military

purposes because they don't put a pilot's life at risk in combat zones.

However, with the advancement of technology, drones can now be produced for

commercial use.

In North America and in other parts of Europe, where

there is the increasing use of the drone, there are guidelines that demand

that drones must stay less than 400 feet above the ground and steering a drone

over someone's house could be considered a trespassing violation.

A drone can also be used for wide ranging activities

including espionage and other activities. In Ghana, it is beginning

to manifest that there isn’t any special regulation for the use of the drone in

spite of an upsurge in the use of the unmanned aerial vehicle. A lot more must

be done to put in place the necessary legal framework that governs the use of

such aerial vehicles to check against abuse.

Our Editorial on Regulating Drones

We carried last week the story of a victim of a drone

incident. The incident which occurred at Kokomlemle was described by

eyewitnesses as frightening.

It emerged later that the drone belonged to the

Brazilian company Queiroz Galvao which was using it in its work.

But the incident should move the authorities to put in

place the regulatory framework for these aerial vehicles which are increasingly

becoming part of the aviation landscape in the country.

A number of companies and individuals now own these

vehicles, but so far there appears to be no proper system for regulating them.

With time, their numbers are sure to increase and if

the country does not act to the control their movement, we are sure to have

confusion in the skies.

Even in the more advanced countries, there have been

troubling incidents involving drones.

Luckily we have been alerted.

The time to take action is now!

Editorial

LET’S ACT NOW

About a year ago, The Insight drew attention to the

danger posed by the acquisition of drones by individuals and companies and we

urged the authorities to take steps to regulate their use.

Nobody paid any attention until a media house allegedly used a drone to film the residence of former President John Dramani Mahama last week-end.

Drones can be weaponised and they pose danger to civil

aviation.

The Insight insists that if the use of drones are not

properly regulated it will soon pose a serious danger to national security.

Our stand on drones has not changed and we call on the

authorities to take appropriate action now to control the use of drones.

We cannot delay on this matter.

Against the Odds:

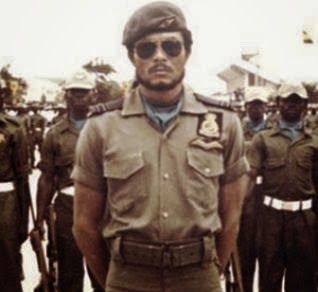

Rawlings and Radical Change in Ghana

|

| Jerry John Rawlings |

By ROAPE

Ghanaian activist and socialist Explo Nani-Kofi

describes his involvement in a period of radicalisation in Ghana in the 1970s

and 1980s. The period found its figurehead in the charismatic leadership of

Flight Lieutenant Jerry Rawlings.

In face of widespread discontent Rawlings

attempted a coup d’état on 15 May 1979, against the military

government led by General Fred Akuffo. The coup failed and Rawlings

was arrested and imprisoned. He began to speak in the language of the left

and attracted the interest and support of Ghanaian socialists and radicals. On

4 June, Rawlings was broken out of jail by soldiers sympathetic to his

politics, he then led a rebellion of the military and civilians against

Akuffo. The Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC) was

established under his leadership, promising to clean-up Ghana of corruption and

injustice.

The AFRC organized an election in September 1979 which was won

by Hilla Limann of the People’s National Party (PNP). The civilian

administration quickly ran into difficulties, of its own making. In 1981, after

a strike wave paralysed the country, the government declared that in the event

of further action all strikers would be arrested. The strike movement helped

precipitate the collapse of the Limann administration. It was clear that the

new democratic government was unable to fulfil its promises of real change

across Ghanaian society. On 31 December 1981 Rawlings, with soldiers and the

support of some left parties, launched a second coup and overthrew the Limann

government. The Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) was set-up

with Rawlings as Chairman. Before long the possibility of radical change in

Ghana gave way to repression of his left-wing allies, and a gradual

retreat from the promises of pro-poor transformation. After several years,

left-wing opponents were imprisoned and at the same time the regime became a

test case for structural adjustment.

Rawlings oversaw the introduction of the

Economic Recovery Programme and called for ‘austerity and sacrifice’. By 1987

Rawlings the revolutionary became the darling of the IMF and the World Bank. In

this ROAPE interview Nani-Kofi explains what some of the experiences were

for activists on the ground.

|

| Explo Nani Kofi |

Can you first of all tell me briefly who

you are and your political background in Ghana?

I am Explo Nani-Kofi and at present the Director of

Kilombo Centre for Civil Society and African Self-Determination which is a

research, education and advocacy institution, which I have been developing as a

social justice practitioner and grass root organiser. Through that I coordinate

the International Conference on Africa, Africa and Social Justice every

September in Peki, Ghana. I come from Peki and was born in Anfoega, both in the

Volta Region of Ghana. When I was a child, relatives, family friends and

neighbours were officials in Kwame Nkrumah’s Convention People’s Party (CPP) so

I grew up in an atmosphere of CPP influence.

In secondary school, I got involved in the Current

Affairs Society and came across The Dawn, published by CPP Overseas, and Amanee

published by Central Union of Ghana Students in Europe, which were Nkrumahist

oriented publications which were being sent discretely into the country. All

this was given as orientation when I was starting secondary school in 1975,

when my teacher was the Marxist-oriented Mahama Bawa. I then founded and became

President of the Students Movement for African Unity (SMAU) in my school,

Mawuli Secondary School in Ho.

Having been in SMAU, when I entered university, I

looked out for the SMAU branch. Initially there was a SMAU note on the notice

board and when I followed it I was introduced to the Pan African Youth Movement

(PANYMO) then led by Chris Buakri Atim. [1] Atim

was the Acting President of the National Union of Ghana students (NUGS) and I

ran errands for him to the other universities often circulating press

statements. By the time of 31 December 1981 coup d’etat, I was the 1st National

Vice President of NUGS.

|

| Dr Kwame Nkrumah |

Can you describe the atmosphere in Ghana at the time,

in the 1970s and 1980s?

On 24 February 1966, the first post-independence

government of Ghana was overthrown through a coup d’etat by police and army

officers of Ghana with what has been shown now to have been influenced by

western intelligence services. Ghana was then ruled by a military junta of the

National Liberation Council (NLC). The NLC organised elections in 1969 which

were won by Dr. K. A, Busia and Progress party (PP) which was the successor

party to the United Party (UP) which was the Right-wing opposition to Kwame

Nkrumah’s government. The Nkrumah regime was the 1st Republic so this became

the 2nd Republic.

The 1970s started with the devaluation of the currency

by 48% on 27 December 1971 after the Pan-African atmosphere created by Kwame

Nkrumah’s government was disrupted by the introduction of the Aliens Compliance

Order policy which expelled Africans from Nigeria, Mali, Niger and other

countries who had been living in Ghana. Radical student movements brought up

the question of the declaration of assets by the politicians of the 2nd

Republic. In response to this situation the right wing government of Dr. Busia

was overthrown by the Ghana Armed Forces. The military government was initially

popular with its Operation Feed Yourself programme, a declaration was made that

we will not pay imperialist imposed debts and we will support African

liberation movements. Gradually, the military regime grew corrupt and

institutionalised the bureaucratic structure in 1975 by dissolving the original

council and replacing it with a council of military generals. The military

regime tried to institutionalise its rule and stop any transfer to civilian

constitutional rule with the campaign for the so-called Union Government. As

the regime became corrupt, the student movement grew more radical.

Before 1976, the external wing of the Ghana students’

movement was led mostly by those who won scholarships to study outside during

Kwame Nkrumah’s regime. In 1976, the external students’ movement (Central Union

of Ghanaian Students in Europe) integrated with the students’ movement back

home under the umbrella of the National Union of Ghana Students (NUGS) and

adopted scientific socialism, which created a crisis as the students’ movement

was a mass organisation of all students in a neo-colonial state and such a

programme and commitment seemed inappropriate.

The students’ movement together with professional

bodies mobilised against the military regime. The students of Ghana had a

national demonstration against the military regime and its Union Government

campaign on 13 May 1977 resulting in the closure of the universities. Since

that day, the week including 13 May each year came to be celebrated as Aluta

Week with demonstrations and other activities. The military regime had a

referendum on its Union Government in 1978 and rigged the referendum results

declaring that the population had endorsed it. Further opposition created a

crisis in the military regime leading to a palace coup that year. In 1979,

during the Aluta Week, a hitherto unknown Air Force Flight Lieutenant by the

name J. J. Rawlings took advantage of Aluta Week and attempted a military

uprising on 15 May 1979 which failed; he was arrested and together with others

brought to trial.

How do you assess the

legacy of Kwame Nkrumah?

Kwame Nkrumah rose to become the main leader of the

struggle against classical colonialism since his return to the Gold Coast, as

Ghana had been named by the colonial power, in 1947 upon invitation by United

Gold Coast Convention. In 1949, he led a breakaway which constituted itself as

the Convention People’s Party and became more rooted in the masses of the

population and was also more radical in its demands for self-government.

Another great plus of his legacy is that the party was national in character

and not dominated by a particular ethnic group as has been a weakness of

certain political parties and ‘nationalist’ movements in other parts of

Africa. As the immediate post-independence government, the Nkrumah

administration embarked on the construction of infrastructure, provision of

social services to the population, developed an industrialisation programme and

provided employment in a way that cannot be compared with any government since.

Kwame Nkrumah’s commitment to African unity, liberation and self-determination

raised his stature throughout the African continent and the African diaspora

triggering a movement for revolutionary Pan-Africanism. He wrote books together

that made an enduring contribution to revolutionary Pan-Africanist theory. All

together this posed a threat to the efforts by the west to continue the

neo-colonial control they had in Africa. As a result of this the CIA influenced

his overthrow on 24 February 1966.

After his overthrow, the political class, including

some who had worked with him, came to a consensus that lacked his vision,

an ‘agreement’ I have referred to as the ‘24 February 1966 Consensus.’ A number

of the leadership and activists of his party integrated with others who had

fallen out with Kwame Nkrumah to constitute new political parties. Any form of

resistance was patchy. Four people were tried for a plot to bring him back to

power. There was a counter coup attempt on 17 April 1967 but it is still

unclear whether it was linked to Nkrumah. The only political party which

departed from this consensus and maintained a genuinely pan-African vision was

the People’s Popular Party led by Dr Willie Kofi Lutterodt and Johnny F. S.

Hansen. This party brought together CPP elements who refused to accept the 24

February coup as a fait accompli and a group of activists with links to

internationalist socialist movement. [2] However,

Nkrumah’s influence developed among a younger generation of activists within

the youth and students. By 1981, there were so many organisations inspired, in

one way or another, by Nkrumah’s legacy and politics.[3]

The conflict between Rawlings and these organisations

during his rule from 1982 to 1992 led to a collapse of many of these

organisations. In lieu of a movement, the dominant application of Nkrumah’s

politics in Ghana today is to use reference to pro-Nkrumah politics to attack

one of the main opposition parties as a group responsible for his overthrow.

That has not helped in practice but has rather been a distraction that creates

confusion about what the emergence of the two main political parties in 1992,

despite their struggle for (and against) Nkrumah’s legacy. What determined the

political divide in 1992 was the attempt to shore up neo-liberal tyranny of

Rawlings regime against the struggle to open the democratic space to enable

genuinely civilian rule. Rawlings regime succeeded in infiltrating the

pro-Nkrumah movement by taking advantage of contacts they had with the left’s

tragic flirting with Rawlings’ fake radicalism in the 1980s. In the process

there are a number of people who were in pro-Nkrumah movements but became

members or supporters of the neo-liberal New Patriotic Party that was founded

in 1992; they saw the NPP as the only effective way to stop the military

regime’s structure reorganising itself into a party under the umbrella of the

National Democratic Congress also set up in 1992.

|

| Jonny Hansen |

You were involved in

the left movement in Ghana. How were you engaged?

I was involved in the Kwame Nkrumah

Revolutionary Guards (KNRG) which emerged as a result of the People’s National

Party, it was perceived as the successor party to Kwame Nkrumah’s Convention

People’s Party. The KNRG was formed by Nkrumahists (adherents Kwame Nkrumah’s

Pan-Africanist and socialist-oriented vision of politics) who were disappointed

in the PNP so decided to organise as Nkrumahists with the guidance of his

revolutionary Pan-Africanism vision of socialist transformation. I also

organised students and youth under the banner of the Students Movement for

Africa Unity (SMAU) which I was a member of since my secondary school days. The

KNRG organised events to mark Kwame Nkrumah’s birthday and memorials for his

death and on those occasions reflected on and analysed the national and

international situation and looked to advance the cause of socialism and

Pan-Africanism. One important forum which brought together all left-wing forces

was the Progressive Forum of 3 October 1981.

From June 1979 to September 1979, the

Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC), under the chairmanship of Flt. Lt.

J. J. Rawlings which was a populist regime and reduced prices, executed

military officers for supposed corruption and was very popular with the radical

forces. This presented a very difficult situation for the successor civilian

regime as the shops had been emptied The experience under the AFRC raised the

expectations of the Ghanaian population which could not be met under civilian

constitutional rule, conditions which were totally different from the populist

military. The situation worked to the advantage of the Rawlings regime as

people developed a sort of euphoria for the AFRC days and therefore Rawlings

became increasingly popular.

There were a number of groups sympathetic

to Rawlings – like June 4 Movement, New Democratic Movement, Movement On

National Affairs, Pan African Youth Movement, People’s Revolutionary League of

Ghana – the majority of these groups became sympathetic with Rawlings

with only the Movement On National Affairs (MONAS) coming out openly against

Rawlings. MONAS supported a call for a probe of the AFRC and also stressed the

anti-communist statements of the AFRC as well as his attacks on Kwame Nkrumah

and support for the overthrow of the Kwame Nkrumah regime. I was close with

groups on both sides with some of my closest friends were in MONAS.[4]

You were involved in

an initiative of setting up workers committees in the Volta region under the

June 4 movement before the 31 December 1981 coup d’etat. Can you give us some

personal background to these initiatives and explain what happened and what

went wrong?

In August 1981, through a meeting involving the June 4

Movement, Pan African Youth Movement and Kwame Nkrumah Revolutionary Guards

with the support of Prof Mawuse Dake a programme of Workers’ Committees was

launched under my coordination.[5] These

were decision-making and mobilisation committees of workers to raise

consciousness and also to work as a group on political issues. These committees

were political discussion groups, they organised community and work places ,

were involved in clean-up activities and also holiday classes for students as

well as revision classes for those who had failed school certificate

examinations and were resitting.

After the 31 December 1981 coup d’etat, the People’s

and Workers Defence Committees were established as organs of popular power.

Chris Atim, under whom I worked in the students’ movement, became a member of

the ruling Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) and national coordinator

of defence committees. He appointed me the Regional Coordinator of the defence

committees in the Volta Region. A former editor of the NUGS, Zaya Yeebo, was

appointed PNDC Secretary for Youth and Sports, I was also appointed the

Regional Political Coordinator of the National Youth Organising Commission.

Being responsible for the defence committees and the youth movement made me the

main contact with mass organisations in the region.

With the help of the committees, we organised the

Defence Committees as units of community and workplace decision making. They

helped with the distribution of goods and services. They arranged to get

implements for work on farms and equipment for fishers. They were also a forum

for political discussion where national and international issues could be

raised by ordinary people.

As this involved the political activity of a left-wing

nature it was mainly based in bigger urban centres like Accra. Yet I made

efforts to get experienced organisers from the capital city of Accra, to assist

us in the Volta Region. I requested the release or secondment of cadres from

the capital. It was in this respect that I worked with Kofi Gafatsi Normanyo

and Kwame Adjimah from the National Secretariat of the Defence Committee in

Accra, and the secondment of Austin Asamoa Tutu from his workplace, the

Architectural and Engineering Services Company (AESC), to work with our

regional secretariat of the Defence Committees.

However, the way we did things was different from how

the bureaucracy wanted things to be done – our involvement directly radicalised

the government. For example, when there was water shortage in the city, we

didn’t see why we should have water where we stayed in student accommodation

whilst ordinary people didn’t have water in town. So we opened our university

accommodation for the ordinary people to come and draw water from the

university. We tried to break down the barriers between ordinary people and

political leaders.

Contradictions in the regime and with its support base

became intolerable. It turned out that the PNDC Chairman, Rawlings, wanted to

have a typical military junta and did not want to see genuine popular organs of

power but to have them just as supporters to shore up the military junta. This

and other issues led to a total breakdown and misunderstanding within the

ruling council on 28 October 1982 and Rawlings felt that he and the two members

of the council most active in the defence committees, Chris Atim and Alolga

Akata Pore, had to go their separate ways but the exact details were not known

to the public, including to organisers like me. After that conflict, Chris Atim

addressed a public rally in Ho where I was based.

When there was a coup attempt to overthrow the PNDC on

23 November 1982 which failed, Rawlings took advantage of the situation to

frame those he considered to be his enemies. In our naivety, many of us

didn’t know that we had been declared enemies. So on 24 November, Rawlings

descended on the official residence of the PNDC Secretary for Youth and Sports

with a helicopter and a fully armed platoon of soldiers. I was there at the

time. He insisted that all of us he found there kneel down in public with guns

cocked at our heads. After that, he declared two of our colleagues – Nicholas

Atampugre and Taata Ofosu – were under arrest and directed the soldiers to take

them away to be detained. Later, on 7 December I was invited to a meeting at

the barracks and when I got there I was arrested and told that the Army

Commander has directed that Kwame Adjimah and I were to be arrested and

detained by the military. With the division in the ruling council, things

started taking regional and ethnic lines. My closeness with Chris Atim, who is

from the North, was interpreted to mean that I was an obstacle to Rawlings

being in control of his home region. It was felt that I had to be removed so

that it would be easier for Rawlings to control his own region. This was a

tragic ethnic turn by the regime.

At the time many saw

Jerry Rawlings together with Thomas Sankara in Burkina Faso, in the north, as

figures committed to radical transformation in Ghana. This was never your

position. Can you explain why you took such a stance on Rawlings? How did you

characterise him (as opposed to Sankara) at that time and now?

There are substantial differences between Rawlings and

Sankara. Sankara was a visionary because he took theoretical study very

seriously as a sympathiser of communist groups in Burkina Faso. This is why we

can quote Sankara today on issues like third world debt, African

self-determination etc. Sankara was also very clear about the anti-imperialist

struggle. Rawlings didn’t have the discipline or the theoretical mind of

Sankara. When Rawlings was recruited into the Free Africa Movement, he saw such

study and discussions as a waste of time and rushed recklessly into an

attempted uprising on 15 May 1979 which failed woefully and put the lives of

all he was associated with in danger. He was a populist who incited the

population without any clear vision of a way out. For those outside Ghana, who

didn’t see his weaknesses, recent revelations that he received financial gifts

from the corrupt Nigerian military tyrant, Sanni Abacha, expose Rawlings’

opportunist character. Facts which are available today show that Rawlings is an

opportunist who had other frustrations with the military authorities. These

included his financial problems as a result of spending too much money on

drinks and his army book shows his difficulties in passing promotion

examinations and even the inability to handle his household responsibilities

that senior officers had to intervene in all these matters.

After a very difficult

period you travelled to Czechoslovakia in 1984 and then to London in 1989. Can

you explain your experiences there? What did it teach you about the communist

bloc? What were your impressions, experience of racism etc?

Having fallen out with the Rawlings government in 1982

I was in military detention until a military uprising and jail break on 19 June

1983 in which political detainees from three major prisons in Ghana and various

military guard rooms managed to escape. I joined the military uprising and jail

break. The military instructed that anybody who saw those of us escaping should

shoot us on sight. Some of my comrades were caught and killed but I was able to

escape to Togo by the end of June that year.

In 1982, I was awarded a scholarship by the

International Union of Students (IUS) to study in Czechoslovakia but I didn’t

take up the award. But once in exile, I appealed to the IUS to revive the award

and they did. As I never wanted to leave Africa I didn’t even have travelling documents.

I had to arrange an emergency Safe Conduct document to join the aeroplane to

Czechoslovakia. As the Eastern European countries were sympathetic to the

Rawlings regime they were unprepared to grant political asylum to opponents of

the Rawlings regime. I lived in Czechoslovakia for one year without residence

permit. Through the award, I went to Czechoslovakia in 1984 to study and

completed my studies in 1989. I was admitted to a PhD programme but as I wasn’t

sure of the post-1989 regime’s support for the IUS, I sought asylum in the UK

where a number of my comrades were in exile.

Despite the official declarations and documents, the

majority of people in Eastern Europe didn’t feel attached to the socialist

governments, certainly not by the 1980s. The ruling class was very unpopular

and treated with scorn as well as being totally alienated from the population

at large. It had a negative effect on many of the foreign students as well. I

was, therefore, not surprised when the experiment collapsed in 1989.

Briefly can you talk

about your life in the UK, your political involvement and activism?

In the UK, I have been active in the left movement.

Initially, we tried to organise the left opposition to Rawlings from London but

the pressures of exile made London the centre for divisions in the Ghanaian

Left. In 1991, a group editing the Revolutionary Banner published in the paper

that Chris Atim and I were agents of the Rawlings’ regime in exile. as a

way of trying to destroy us through a smear campaign. With the collapse of the

Ghana left, I participated actively in the general left movement in UK. I was a

member of the Stop the War Coalition Steering Committees for 5 years. I

contested the Greater London Assembly Elections in 2008 on the left platform –

Left List.

How have you

maintained your involvement in African politics and movements?

In London, I was the Secretary of the

Afrika United Action Front which was a coalition of Pan-Africanist

organisations. I was also the coordinator of the Kwame Nkrumah Memorial

Lectures, the International Campaign to Un-ban Kwame Nkrumah’s Convention People’s

Party, IMF & World Bank Wanted for Fraud Campaign, Campaign Against Proxy

War in Africa and the African Liberation Support Campaign Network. I also

managed and edited a pan-Africanist journal known as the Kilombo Pan-African

Community Journal. Through these roles I networked with others involved in

African politics and movements.[6]

What are some of the

principle challenges to a radical agenda and politics on the continent? What

sort of projects are needed?

Until recently, a lot of the post-colonial world was

looking to Latin America as a model to address the issue of neo-colonialism.

Recent developments there give us further lessons, the importance of winning over

and being rooted in the population at large and knowing that the capitalist

class will always be on the offensive to stall efforts at social justice.

In Africa, liberation movements have either not been

able to adjust to administering and managing or have been overwhelmed by the

reality of the post-colonial state. The left or radical forces seem to have

been cast to the margins and even those who were once major forces have become

a shadow of their former selves.

I’ll often return to a definition between left and

right by Emmanuel Hansen in his analysis of Ghana at the time of the 31

December 1981 coup d’etat where he wrote: “Among progressive groups and

individuals there had for some time existed the idea that Ghana’s post-colonial

problems were such that only a revolution could change them. What exactly this

revolution was to imply has never been precisely articulated. There is,

however, a consensus that it involves termination of the control of the local

economy by foreign multinational companies, changes in the structure of

production and production relations, changes in the class structure of control

of the state, creation of political forms which would make the interests of the

broad masses of people predominant and realisable and a programme which would

initiate a process of improving the material conditions of the mass of the

people. Those who broadly shared this position I would identify as belonging to

the left. Those who entertained the opposite position that there was nothing

basically wrong with the nature of the country’s structure of production or

production relations or the nature of economic relations with Western

capitalist countries or the structure of power, class relations or the nature

of state power, and that only certain aspects of its functioning needed to be

reformed. I would identify as the right.” I think Hansen is correct and I have

long seen myself as being part of the ‘left’ in this definition.

Can you explain,

through the long period of exile and hardships you faced in Ghana,

Czechoslovakia and UK – witnessing as you did the murder of comrades – how you

managed to survive? What forces in your life keep you going?

My father was imprisoned by the PNDC and my mother had

traveled to the Republic of Togo when the PNDC took over with my younger

siblings. In these difficulties I put the commitment to the cause above

personal pain and I have never lost that internal driving force. When I fled

into exile, my mother was with me, and when she was returning to Ghana, she

told me that if she was arrested as a tactic of the regime to lure me back to

Ghana, that I should never return and that she was prepared to die. My family’s

support has strengthened me. My comrades who have been murdered haven’t done

anything that I have not done, I was supposed to die with them. I think the

only tribute I can pay to them is to continue on the path we were on before

they were murdered. The other thing that keeps me going materially and

psychologically is the unlimited generosity I have had from a number of

compatriots. In addition to this, is the recognition I receive from comrades

for my contribution to the development of the broad left In Ghana. All these

strengthen my commitment.]

Explo Nani-Kofi was born in Ghana where he

started his activist as a socialist organizer for popular democracy. He

coordinated the Campaign Against Proxy War in Africa and the IMF-World Bank

Wanted For Fraud Campaign. He is Director of the Kilombo Centre for Civil Society

and African Self-Determination, in Peki, Ghana and London, UK.

Notes

[1] Chris

Bukari Atim later became co-plotter with J. J. Rawlings in the 31 December 1981

coup in Ghana and also a leading member of the ruling Provisional National

Defence Council (PNDC).

[3]

These groups included the African Youth Brigade, African Youth Command, June 4

Movement, Kwame Nkrumah Revolutionary Guards, Kwame Nkrumah Youth League

(formerly part of the People’s National Party Youth League), Movement On

National Affairs, New Democratic Movement, Pan African Youth Movement, People’s

Revolutionary League of Ghana, Socialist Revolutionary League of Ghana, Students

Movement for African Unity each had an orientation close to Kwame Nkrumah’s

vision.

[4] My

closest friend and comrade was Kwasi Agbley and was the International Affairs

Spokesman of MONAS and was arrested when the PNDC came into office and was

imprisoned in the military detention cells and later the Nsawam Medium Security

Prisons, the most notorious prison in Ghana for almost two years. We were both

students of Mahama Bawa, who was the Secretary for the State Commission for

Economic Cooperation under the PNDC. When the Left came into conflict with

Rawlings, our teacher, Bawa, was in the Castle military detention cell and I

was in military detention.

[5] Mawuse

Dake was a progressive politician who was a Vice Presidential candidate of a

political party in general elections in Ghana in 1979 called the Social

Democratic Front (SDF) and became a minister in the PNDC regime but like most

left-wing activists fell out with Rawlings.

[6] Most

literature on the history of the left ignore the 1930s when the trade union

movement started and the Communist International sponsored Negro Worker

publication. During the period the West African Youth League led by I. T. A.

Wallace Johnson emerged linked with the Communist International. Some UK based Ghanaians

also joined the Socialist Party of Great Britain and the Communist Party of

Great Britain (CPGB). It is difficult to say whether those involved became

integrated with the CPP but there is evidence that some of the activists in the

trade unions fell out with the CPP between 1952 and 1954.

No comments:

Post a Comment