|

| Dr Kwesi Botchwey |

By Ekow Mensah

The much hyped leaked report of the Kwesi Botchwey

Committee is nothing more or less than fake news being deliberately circulated

to dissuade former President John Dramani Mahama from offering himself as

Presidential Candidate of the National Democratic Congress (NDC).

Over the last couple of days, various media houses have

claimed that they have seen copies of a 67-page report blaming former President

Mahama for the defeat of the NDC in the 2016 elections.

However, checks by “The Insight” have revealed that no

such report exists.

NDC General Secretary Johnson Aseidu Nketia was emphatic

that the leaders of the party have not received any such report from the Kwesi

Botchwey Committee.

Some members of the Committee who spoke to “The Insight”

also said that the report of the Committee is not ready and therefore could not

have been leaked.

The Kwesi Botchwey Committee was set up by the National

Executive Committee of the Party to find out why the party lost the 2016

elections.

So far, it has toured the country to listen to party

leaders and cadres in addition to engaging officials and elders of the party.

There are very strong indications that former President

Mahama will join the contest for the presidential candidature of the NDC even

though he has repeatedly said that he has not made up his mind.

Party stalwarts including Hannah Tetteh, former Minister

of Foreign Affairs, Okudzeto Ablakwa, former Deputy Minister of Education and

Kofi Adams, National Organiser have all said that the former President is the

best bet for the NDC for the 2020 elections.

Editorial

KUME

PREKO

The anniversary of the Kume Preko demonstration has

passed without fanfare even though President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo was

one of the key figures who organised it on May 11, 1995.

Perhaps being in government is so very different from

being in opposition and therefore the things to highlight today may be also

different from what was focused on yesterday.

The Kume Preko demonstration brought out an estimated

120,000 people into the streets of Accra to demand the abolition of the Value

Added Tax (VAT) and an end to the economic and social hardship facing the

people of Ghana.

The protest was against increasing petroleum prices,

very high utility tariffs and high school fees.

As far as we are concerned the most important lesson of

the Kume Preko protest is that no government can fool the masses all the time

and that Governments which fail to meet the aspirations of the people will

incur their wrath.

The spirit of Kume Preko will continue to live on until

true democracy is firmly established in Ghana.

Local News:

'Second revival

coming to Komenda sugar factory'

The Akufo-Addo government has assured, it will revive

the Komenda Sugar factory after it was shut down last year for reasons blamed

on the former government's poor economic judgment.

Deputy Trade Minister Carlos Kingsley Ahenkorah told

Joy News, government is 'working frantically' to get operational, a $24m

factory which worked for barely 4 weeks after it was commissioned.

While holding out a promised revival, the politician

could not help but take a swipe at the previous NDC government for

"putting up a factory when you don't actually have raw materials".

The Komenda Sugar factory became a sour point of

controversy over its viability after some traditional pomp.

Commissioned seven months to a crucial election, the

opposition NPP described it as a vote-buying ploy.

Critics lined up to stress the factory will produce more 'propaganda than sugar'. They said building a plant without a guaranteed supply of raw

materials is putting the cart before the horse.

But the Mahama government stayed the course,

defending the project touted to create 7,000 direct and indirect jobs in one of

Ghana's poorest regions, the Central region.

It was explained, 60% of the needed sugarcane will

bought from farmers within the catchment area and 40% will be supplied by the

company's own farms which had reached nursery stage.

After pushing out some bags of sugar, the factory

inaugurated May 30 2016 was shut down by June 24. A move explained as routine

maintenance.

A promise to get the factory operation in October was postponed to November until a change in government in December ended any further

assurances from the Mahama administration.

Taking over the baton of assurances, the Deputy Trade

minister and Tema West MP said the new government is holding talks on fixing

the project's faulty economic foundation.

When the factory is ready to work again, the

government will tell the story of Komenda's misfortune all over again, he said.

Built in the 60's, liquidated in 1995, the factory's

first resurrection happened in 2016. Revamped in 2016, defunct again in 2016,

there is a new promise of a second and final resurrection - hopefully.

Ghana:

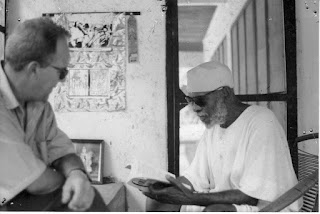

Kofi Ghanaba; Afro

Jazz legend and the first African to present for the BBC

|

| Collins with Kofi Ghanaba |

I watched with intense concentration as the flames

shot up with white smoke swirling into the clear bright sky. My thoughts

wandered and went to Chicago USA to a struggling African musician who was

trying to get his music heard. He was in good company as most of the Jazz

musicians of that era were also going through the same frustrations of the

industry.

Guy warren brought his Bintin Obonu (Talking Drum)

into American Jazz. It was an introduction which earned him a residency at the

African Room and took him off the cold windy streets of Chicago. At the African

room, Guy found his voice, he had put together a small group that was blowing

audiences away night after night. He was writing and playing his own material

and his drumming was causing a School rather abruptly, Guy Warren decided to

follow what his heart desired most, Jazz.

In the early 50’s he had a spell with the ET Mensah

Tempo band which he had led and then moved to London and joined Kenny Grahams

Afro-Cubists where he became an influential and well sought after Bongo player.

He presented programs on BBC the famous “Calling West

Africa” (the first African to present for the British Broadcasting

Corporation). It was from here that he journeyed to the shores of America

pursuing the desire to record his music. Guy persevered and went hungry on many

a night . Knocking on doors all the time in relentless pursuit of getting his

music on record. Through the wife of a fellow musician he got a lucky

introduction to an old Jazz musician Red Sanders who instantly took to Guys

music. Red Sanders decided he would fund the recording as long as he was

allowed to play on it.

It didn’t sit well with Guys sideman and faithful

friend Genero Esposito. The deal for the album was made by Red Sanders who cut

himself into the contract with Decca . Despite Guys misgivings he still thought

it has a good chance to have his music recorded.

The album was recorded with a lot of difficulty with

Guy going through a series of session men who couldn’t play his music. He

eventually settled on a few and the Album was recorded and released.

A year after the album’s release Guy was still broke

and starving. The band had broken up and he was looking for work again. After

knocking on several doors he eventually found a place in African Room where his

Guy Warren sounds enjoyed a residency. It was from the African Room that Guys

fame spread.

He had introduced for the first time the Bintin Obonu

drum (Talking drum) into Jazz and was mesmerizing audiences with his style of

Jazz drumming. He blew away Americans great jazz drummer of the time Maxx Roach

and great drummers like Willy Jones who greatly admired his playing. Max Roach

was so incredulous of Guys drumming to the point that he refused to believe Guy

had played all the drums on “The Lardy Marie Drum Suite. Guy was in the mix

from here on. His musical encounters with contemporaries like the great Charlie

Parker (Bird) Clifford Brown, Ritchie Ponell, Hark Mobley, Abbey Lincoln.

Billie Holiday, Miles Davies, Lester Young and many more reads like a who is

who of Jazz.

The song “Happy Feeling” was the hit off the

album and caught worldwide attention when it was covered by Englebert

Humperdick the German Orchestrator and went to No 1 in the billboard charts.

Guy followed the success of African Speaks America

Answers with another recording “Themes for Africa Drums”. Guy Warren recorded a

total of 10 Albums on labels like Decca, RCA Victor, leading labels of this

era.(see discography for full list).

Guy was emphatic about his African identity even in

the hard times of the 50’s when African s were called Negroes and were conking

their hair. He insisted on donning his African costume and sat proud behind his

drums.

His insistence on this African identity earned him a

close personal relationship with the Osagyefo Kwame Nkrumah the first president

of Ghana who was espousing the African Personality. Guy much later on in his

life asserted this further by dropping his rather western name Guy Warren for

the name Kofi Ghanaba which means the son of Ghana

In the Who is Who of Jazz 1957, Leonard Feather Jazz

critic write, “Guy has a detailed and authentic knowledge of African rhythms

and dance which he uses in his playing”.

Ghanaba’s Seminal album “Africa Speaks America Answers

defined the way in which African music will be seen and directly influenced the

music and musicians of Africa. The music of Osibisa, Fela Anikulapo Kuti, Hugh

Masekela and Man Dibango to name a few were very much influenced by this album.

When you listen to the opening track of Osibisa’s debut album “The Dawn” you

get a good sense of the direction. The heavy grooves of the track “Highlife”

have been replicated over the years by many an Afro Rock or Afro Jazz musician.

Ghanaba’s influence looms large over the music of Africa in many ways as he

took the drum music of Africa to another level hitherto unheard of. A lot of

wildlife documentaries frequently use his music in the background as well.

The greatness of this man’s contribution is

inestimable. He is the first African to be listed in the Encyclopedia of Jazz.

In the Who is Who of Jazz and the first African member of ASCAP (American

Society of Composers Authorized and Publishers).

Ghanaba’s experiments with African drums continued on

his return to Ghana and until his death ,He had the title of Odomankoma Kyerema

meaning “The Divine Drummer” bestowed on him. He continued to perform

into his 80’s and his last performance at age 86 was two weeks before his

passing at the Goethe Institute in Accra at which he also delivered a lecture

on “the African presence in Jazz” I watched the smoke swirl up to the clear

skies and my thoughts came back with a smile and a thought, this great son of

Africa was off to play the great Fontomfroms (the massive twin drums of the

Akan people of Ghana) in the heavens. Ding-Dong!

Source: Scratch Magazine

Africa:

History: How African Muslims

“civilized Spain”

|

| The Moors |

The Moors invaded Spain in 711 AD and African Muslims literally

civilized the wild, white tribes. Recent scholarship now sheds new light on how

Moorish advances in mathematics, astronomy, art, and philosophy helped propel

Europe out of the Dark Ages and into the Renaissance.

Four hundred and eight years ago today King

Phillip III of Spain signed an order, which was one of the earliest

examples of ethnic cleansing. At the height of the Spanish inquisition, King

Phillip III ordered the expulsion of 300,000 Muslim Moriscos, which initiated

one of the most brutal and tragic episodes in the history of Spain.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, it was ancient

Africans that brought civilization to Spain and large parts of Europe and not

the other way around.

The first civilization of Europe was established on

the Greek island of Crete in 1700 BC and the Greeks were primarily civilized by

the Black Africans of the Nile Valley. The Greeks then passed on this acquired

culture to the Romans who ultimately lost it; thus, initiating the Dark Ages

that lasted for five centuries. Civilization was once again reintroduced to

Europe when another group of Black Africans, The Moors, brought the Dark Ages

to an end.

When history is taught in the West, the period called

the “Middle Ages” is generally referred to as the “Dark Ages,” and depicted as

the period during which civilization in general, including the arts and

sciences, laid somewhat idle. This was certainly true for Europeans, but not

for Africans.

Renowned historian, Cheikh Anta Diop, explains how

during the Middle Ages, the great empires of the world were Black empires, and

the educational and cultural centers of the world were predominately African.

Moreover, during that period, it was the Europeans who were the lawless

barbarians.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire multitudes of

white warring tribes from the Caucasus were pushed into Western Europe by the

invading Huns. The Moors invaded Spanish shores in 711 AD and African Muslims

literally civilized the wild, white tribes from the Caucus. The Moors

eventually ruled over Spain, Portugal, North Africa and southern France for

over seven hundred years.

Although generations of Spanish rulers have tried to

expunge this era from the historical record, recent archaeology and scholarship

now sheds new light on how Moorish advances in mathematics, astronomy, art, and

philosophy helped propel Europe out of the Dark Ages and into the Renaissance.

One the most famous British historians, Basil

Davidson, noted that during the eighth century there was no land “more admired

by its neighbours, or more comfortable to live in, than a rich African

civilization which took shape in Spain”.

The Moors were unquestionably Black and the 16th

century English playwright William Shakespeare used the word Moor as a synonym

for African.

Education was universal in Muslim Spain, while in

Christian Europe, 99 percent of the population was illiterate, and even kings

could neither read nor write. The Moors boasted a remarkably high literacy rate

for a pre-modern society. During an era when Europe had only two universities,

the Moors had seventeen. The founders of Oxford University were inspired to

form the institution after visiting universities in Spain. According to the

United Nations’ Education body, the oldest university operating in the world today

is the University of Al-Karaouine of Morocco founded during the height of the

Moorish Empire in 859 A.D. by a Black woman named Fatima al-Fihri.

In the realm of mathematics, the number zero (0), the

Arabic numerals, and the decimal system were all introduced to Europe by

Muslims, assisting them to solve problems far more quickly and accurately and

laying the foundation for the Scientific Revolution.

The Moors’ scientific curiosity extended to flight and

polymath. Ibn Firnas made the world’s first scientific attempt to fly in a

controlled manner in 875 A.D. Historical archives suggest that his attempt

worked, but his landing was somewhat less successful. Africans took to the

skies some six centuries before the Italian Leonardo Da Vinci developed a hang glider.

Clearly, the Moors helped to lift the general European

populace out of the Dark Ages, and paved the way for the Renaissance period. In

fact, a large number of the traits on which modern Europe prides itself came to

it from Muslim Spain, namely, free trade, diplomacy, open borders, etiquette,

advanced seafaring, research methods, and key advances in chemistry.

At a time when the Moors built 600 public baths and

the rulers lived in sumptuous palaces, the monarchs of Germany, France, and

England convinced their subjects that cleanliness was a sin and European kings

dwelt in big barns, with no windows and no chimneys, often with only a hole in

the roof for the exit of smoke.

In the 10th century, Cordoba was not just the capital

of Moorish Spain but also the most important and modern city in Europe.

Cordoba boasted a population of half a million and had street lighting, fifty

hospitals with running water, five hundred mosques and seventy libraries, one

of which held over 500,000 books.

All of these achievements occurred at a time when

London had a predominantly illiterate population of around 20,000 and had

largely forgotten the technical advances of the Romans some six hundred years

before. Street lamps and paved streets did not appear in London or Paris until

hundreds of years later.

The Catholic Church forbade money lending which

severely hampered any efforts at economic progress. Medieval Christian Europe

was a miserable lot, which was rife with squalor, barbarism, illiteracy, and

mysticism.

In Europe’s great Age of Exploration, Spain and

Portugal were the leaders in global seafaring. It was the Moorish advances in

navigational technology such as the astrolabe and sextant, as well as their

improvements in cartography and shipbuilding, that paved the way for the Age of

Exploration. Thus, the era of Western global dominance of the past

half-millennium originated from the African Moorish sailors of the Iberian

Peninsula during the 1300s.

Long before Spanish Monarchs commissioned Columbus’

search for land to the West, African Muslims, amongst others, had long since

established significant contact with the Americas and left a lasting impression

on Native culture.

One can only wonder how Columbus could have

‘discovered’ America when a highly civilised and sophisticated people were

watching him arrive from America’s shores?

An overwhelming body of new evidence is emerging which

proves that Africans had frequently sailed across the Atlantic to the Americas,

many years before Columbus and indeed before Christ. Dr. Barry Fell of Harvard

University highlights an array of evidence of Muslims in America before

Columbus from sculptures, oral traditions, coins, eye-witness reports, ancient

artifacts, Arabic documents and inscriptions.

The strongest evidence of African presence in America

before Columbus comes from the pen of Columbus himself. In 1920, a renowned

American historian and linguist, Leo Weiner of Harvard University, in his

book, Africa and the Discovery of America, explained how Columbus noted in

his journal that Native Americans had confirmed that,“black skinned people had

come from the south-east in boats, trading in gold-tipped spears.”

Muslim Spain not only collected and perpetuated the

intellectual advances of Ancient Egypt, Greece and Roman civilisation, it also

expanded on that civilisation and made its own vital contributions in fields

ranging from astronomy, pharmacology, maritime navigation, architecture and

law.

The centuries old impression given by some Western

scholars that the African continent made little or no contributions to

civilization, and that its people are naturally primitive has, unfortunately,

became the basis of racial prejudice, slavery, colonialism and the ongoing

economic oppression of Africa. If Africans re-write their true history, they

will reveal a glory that they will inevitably seek to recapture. After all, the

greatest threat towards Africa having a glorious future is her people’s

ignorance of Africa’s glorious past.

* Garikai Chengu is a scholar at Harvard University.

Contact him on garikai.chengu@gmail.com. This article previously appeared in Global Research.

Source: Pambazuka

Feature:

Africa in the 21st century: Legacy of

imperialism and development prospects

Some arguments made today on why Africa cannot catch

up with the West were also made 100 years ago when Africa was under European

colonization, with the colonizers blaming everything but imperialism as the

root cause of underdevelopment. The world economic structure has not changed,

no matter the rhetoric of globalization. Africa remains semi-colonial:

increasingly dependent on developed countries for overvalued manufactured goods

while exporting raw materials at prices determined by commodity markets in the

West.

Abstract

This essay argues that Africa is undergoing changes in

its economies in the 21st century, not only because of the role that China is

playing but owing to intense competition from other Western countries and the

Middle East. China’s role is within the capitalist world economy and within the

patron-client model of integration that the Europeans followed after African

countries achieved their formal independence from colonization. During the

second half of the 20th century, northwest Europe remained the conduit for

African integration into the US-centered global economy, despite the role of

US-based multinational corporations. According to Pew Research Center polls of

African nations, the issue concerning the vast majority of the people remains

the gap between the rich and poor. This is directly related to the

international competition for market share in Africa as well as the security

issue intertwined with local rebels groups and what the US labels

Islamic-inspired “terrorism”, or another form of guerrilla warfare. This essay

examines many of these issues for a deep understanding of Africa today and its

future prospects.

Part I: Structural

obstacles to development and social justice

Decades after the decolonization of Africa and after

Frantz Fanon (Wretched of the Earth) depicted the social, economic, political

and cultural problems associated with the legacy of colonialism there has been

no structural change in the political economy of the 54 African nation-states

any more than in ending endemic poverty as the UN and other organizations have

been promising for decades or closing the rich-poor gap. It is misleading and a

remnant of imperialist political labeling to lump all African countries under

one category, just as it is misleading to place all of Latin American countries

in a single category, although they do have common characteristics and a common

legacy of colonialism and the current reality of foreign control of resources

and market share.

There is a huge difference between South Africa now

part of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) economy, and Somalia

ranking as one of the world’s poorest nations with political instability and

dim prospects for economic growth. It is just as difficult to make comparisons

between Islamic North Africa with sub-Sahara Africa, despite political

instability that is a common characteristic in most as the continuation of

foreign economic dependence after the end of colonial rule. With this caveat in

mind, for purposes of this very short essay I will address some common features

and note differences as well in development models.

Apologists of capitalism argue that Africa’s current

problems are strictly cyclical because the prices of metals, oil and other

commodities, especially coffee and cocoa, have been declining amid a

deflationary international climate. While it is true that the slowdown in

commodities demand in China has obviously impacted Africa, the majority of the

people were not better off when prices were rising. Regardless of capitalism’s

expansion and contraction cycles, from the 1950s to the present, living

standards for the African people have not improved, no matter the lofty claims

from Western governments, NGOs and other organizations about helping Africa

become self-sufficient.

In the second half of the 20th century, Africa’s

division of labor and national institutions – everything from military to

banking and foreign trade - was largely determined by the core countries - US

and northwest Europe - with the considerable assistance from the International

Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank and its affiliates, African Development Bank

and a number of United Nations agencies, and of course, the explosion of NGOs

some of which are fully funded by governments trying to peddle political and

economic influence. In short, the external mechanisms of Africa’s dependence

became stronger and more solidified in the last six decades than they were

during the era of colonial rule.

In fact, there has been a downward trend in living

standards for the vast majority of Africans from 1990 to 2015, despite the

remarkable uptrend cycle in commodity prices and massive new investment from

China. This is evident by examining all indicators from life expectancy to

access to clean water and sanitation. There are those who point to periodic

drought primarily in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia; local wars and rebel

conflicts in the drought-stricken countries as well as others especially where

Muslims have influence such as Sudan, Nigeria, and Libya.

Besides endemic poverty that creates fertile grounds

for Islamic or community inspired rebel movements throughout many parts of the

continent, the population explosion, corrupt politicians, contraband and

informal economy, absence of infrastructural development, and modern technology

to help the continent achieve capitalist development comparable to that of the

West are obstacles to progress. It is noteworthy that some of the arguments

made today on why Africa cannot catch up with its Western counterparts were

also made one hundred years ago when Africa was under European colonization,

with the colonizers blaming everything but imperialism as the root cause of

underdevelopment.

One cause for the systemic underdevelopment of Africa

has been and remains that more capital flows out than comes in, invariably

foreign loans having the role as catalysts to the process of de-capitalization.

The cycle of public foreign debt and de-capitalization continues across the

continent under the watchful eye of the International Monetary Fund and foreign

financial institutions that represent big banks in the US and Europe and large

corporate interests.

It is, indeed, a monumental step forward that Africans

have served as heads of the United Nations and in key positions of

international organizations. From a symbolic perspective, it was great to see

Kofi Annan as the UN secretary-general, but was Africa better off when he left

the UN than when he came in; or was there any structural change in the

political economy of the entire continent from Egypt to South Africa, from

Nigeria to Kenya? Inordinate dependence on the foreign–dominated and

outward-oriented primary sector of production owing to failure to diversify the

economy remains the major obstacle to raising living standards.

Many observers of the African political economy argue

that there have been success stories, among them South Africa freeing itself

from white minority political rule though keeping white minority economic

hegemony. With the exception of Israel and rightwing elements in the US, the

entire world celebrated the end of South Africa’s apartheid a generation ago.

Nelson Mandela became a symbol of freedom and self-determination for Africans.

However, high unemployment, low living standards among blacks, lack of upward

mobility, and the rich-poor divide persist, with the country occupying the

world’s last place for life expectancy.

Although South Africa was on its way to catching up

with Brazil, India and Russia, enjoying 38 per cent GDP growth in the last

decade, this was not indicative of social mobility but rather capital

concentration. In 2015, South Africa suffered unemployment at the same level as

Greece that has been under IMF-EU austerity since 2010. Socioeconomic and

political conditions are worse in the rest of Africa, and this includes Muslim

northern Africa that has suffered US-NATO direct and indirect military

interference in its social uprisings during the Arab Spring revolts that once

represented the promise of a democratic Africa free of dictators linked to

large domestic and foreign capitalists.

Judging from the unemployment statistics in Africa’s

two largest economies, Nigeria and South Africa, both dependent on extractive

industry exports, there is not much difference between them, with all of those

natural resources, and Greece suffering five consecutive years of

IMF-EU-imposed austerity and downward socioeconomic mobility. One could argue

that 26.4 per cent unemployment for South Africa and 24 per cent for Nigeria

are understandable owing to the cyclical nature of the commodities market –

both gold and crude oil are sharply down from their highs, along with all

commodities. However, the core issue is not capitalism’s cyclical contraction,

but the high levels of structural unemployment and underemployment in the

continent’s richest countries, as well as the vast income gap between the very

few wealthy individuals and the vast majority of the masses.

Obstacles to development account for a division of

labor that has remained about the same in the last half-century. This is

despite reductions in extreme poverty (under two dollars a day category) in the

last two decades. By all indications, globalization has accounted for the

downward mobility of most Africans, although this may not be as clear when

looking at GDP statistics of certain countries, including South Africa and

Nigeria. The world economic structure has not changed, no matter the rhetoric

about globalization and neoliberal policies uplifting all economies across the

world. Just the opposite, the overall economic picture of Africa is one of

steady decline since the 1980s. The continent’s share of global trade was 3.1

per cent in 1955 and in 1990 it was a mere 1.2 per cent.

Largely because of China as a major new player in the

region’s trade, there was a rise after the recession of the early 1990s, but

this too was limited to the primary sector of production. The China factor did

not help the continent lift its GDP amounting to under $300 billion in 1997

while the debt was $315 billion. This allowed the IMF to impose austerity and

neoliberal measures of privatization, corporate tax reductions, and trade

barrier removals that further weakened the national economies. The austerity

measures not only prevented upward socioeconomic mobility, but actually drove

more people into lower living standards.

In December 1993,UN secretary-general Boutros-Boutrros

Ghali argued that the solution for Africa’s socioeconomic problems rested with

greater integration. In an essay on this issue, Robert J. Cummings noted that:

“From the 1950s to the present, more than 200 organizations have been founded

on the continent of Africa for the purpose of fostering regional and

sub-regional integration and economic cooperation. The performance record of

these myriad organizations historically have not been sterling.” (R. J.

Cummings “Africa’s Case for Economic Integration” (www.HU Archives.net )

The efforts on the part of the UN, World Bank and

other Western institutions and governments to forge African integration have

not altered the dependent structure of the economy based on the primary sector

of production nor have such efforts resulted in higher living standards and

upward social mobility despite some reduction in poverty in the last two

decades. Integration on the patron-client model is at the core of

neo-colonialism in Africa and favors the multinational corporations, thus

perpetuating external dependence and underdevelopment.

The most significant challenge for Africa in the next

few decades will be to transform itself from a largely "dependent

outward-oriented" economy (primary sector production exports) providing

cheap raw materials for the advanced capitalist countries to an inward-looking

(producing to meet domestic demand through import substitution

industrialization) integrated via an intra-continental model and developing

more equitable terms of trade with developed countries. The uneven terms of

trade, the inherent lower value of African exports vs. its imports from the

developed countries has been and remains a core problem in development.

To achieve the goal of self-sufficiency Africa would

need more than NGOs and UN intervention that only target emergency areas during

war and famine. Africa would need more than China funding infrastructural

development intended to accommodate extractive mining and agricultural regions,

and more than regional integration that the World Bank has been advocating and

without success by its own admission, and only intended to strengthen the role

of multinational corporations trying to dominate key sectors of the raw

materials economy.

In the absence of a systemic political change, just as

took place in England (1689) and France (1789) that paved the way for economic

modernization, Africa cannot achieve its goal of self-sufficiency no matter the

rhetoric by politicians on the continent or Western organizations like the

World Bank and corporations employing the self-sufficiency rhetoric but

operating as imperialists not much different in results than the colonialists

of the 19th century.

Part II: China’s economic role in Africa

Is China threatening to displace the Europeans from

Africa at some point in the second half of the 21st century, as the mass media

in the US has been hinting since the global recession of 2008? Or is EU-Chinese

capital so intertwined that what may be counted as China’s market share in

Africa could very well be yielding profits for French, British and German

multinational corporations? If capitalist China is such a threat to the West,

why has the very Western World Bank been collaborating with China on a number

of fronts? Is it merely the fear of the US that China as the inevitable number

one economic power in the world will corner the most abundant and cheapest

markets in Africa?

In 2010, Wikileaks published the US concern about

China helping to develop the infrastructure strategically in those countries in

Africa where it plans to do business. Two things alarmed the US: a) no strings

attached to infrastructural development, at least no direct strings as the US

and EU always impose on the recipient country; and b) the clever way the

Chinese are including the World Bank and European governments and EU-based

multinational corporations. In short, China’s multilateralism as a strategy of

securing market share has been upsetting to American unilateralists who see a

fiendish plan that would entail Africa transferring its historical dependence

from the West to East.

Another issue regarding China is the scope of its role

in Africa in 2015, considering that the Western media present it as hegemonic

and potentially threatening to “US and Western interests”, thus invoking

national and trade bloc capitalism as a populist tactic. In reality, as we will

see below, China currently has a small role while the Europeans, US and

wealthier Gulf Arab states enjoy the lion’s share of the market.

What has alarmed the Western capitalists and

politicians is the reality that African exports to China went from a mere 1 per

cent of world share in 2000 to 15 per cent in 2012, and are likely to continue

rising for the indefinite future. Despite the inevitable cyclical economic

slowdown in China, it is just as inevitable that by the 2030s we can safely

predict much closer trade, investment and overall economic dependency of Africa

on China. This in itself poses not just a threat to Western capitalism but to

Western geopolitical designs on a continent very rich in natural resources.

Because the US does not compete with China in Africa using the same tools of

economic integration, about the only response the US has is to flex its

military muscle and secure as much as it can for US-based multinational

corporations.

Before we assume China’s role is benign, the issue of

China as the panacea for Africa is one that many have emphasized, given that

European and US economic, military and political roles throughout Africa have

not resulted in improvements as judged by standards the West has been

proclaiming – democracy, freedom, economic development and higher living

standards. Some observers in and outside of Africa believe that China’s

integration model, which starts with infrastructural development that would

help the domestic economy as well as forge greater regional integration while

stimulating the export sector, is promising. After all, the European

imperialists had done nothing but pillage Africa from the start of the

trans-Atlantic slave trade in the 15th century when the Portuguese landed until

the more subtle late 20th century policies of assisting corporate exploitation

of natural resources. Moreover, if China is so well integrated into the global

economy and it is helping to forge a new integration model in Africa, this

presents new opportunities for African counties, at least for those rich in

natural resources.

The bottom line is whether China will help Africa

develop or merely perpetuate underdevelopment as did the Europeans and the US.

Underdevelopment is a process, just as development, that takes place amid

domestic and international political economy dynamics. Development is not a

matter of a country having a surplus labor force, or having near

self-sufficiency in minerals and raw materials, or enjoying an infrastructure

that can accommodate rapid development to buttress the capital-intensive export

sector mostly of extractive industries. Africa is one of the richest continents

on the planet in natural resources and it certainly has a surplus labor force

at the lowest cost on the planet in comparison with the other continents. Can

Chinese investment do something with these cheap assets to help itself while

also helping Africa?

In order to secure a segment of Africa’s natural

resources for its own growth and development at the lowest possible cost, China

has been investing in the continent and counting on it for rapid export growth

in the 21st century. Despite its rich resources and new investment from China

as well as Gulf Arab countries, Europe and US, the persistence of

underdevelopment in Africa defies logic at least on the surface beyond the GDP

growth numbers and marginal decline in extreme poverty. Why is there reason to

believe the Chinese will change a history of five centuries of colonialism and

neo-colonialism?

One could argue that the structural causes have

everything to do with the corrupt and incompetent political regimes combined

with the uneven development complicated by the periodic famines and droughts in

a number of sub-Saharan regions. Another argument that the apologists of

globalization and neoliberal politics make is that Africa has not fully

integrated into the world capitalist economy, leaving much of its productive

capacities underutilized or outside the domain of international trade owing to

persistence of tribalism. Is Africa’s problem underutilization of natural

resources, or uneven terms of trade, chronic exploitation of low labor values,

massive capital concentration in the hands of very few comprador bourgeoisie

linked to foreign capital, and of course corrupt politicians that foreign

corporations bribe to secure contracts?

Another issue that Western analysts are constantly

making is that there is instability owing to civil conflicts in a number of

countries, from Sudan and Nigeria to Central and East Africa where rebels are

an obstacle to stability and development. In the Islamic countries north of the

Sahara, there is the instability caused by jihadist elements as there is in the

East; activities which also impact Africa more broadly. However, jihadist

conditions, as we will see below, are of fairly recent origin and even so a

reaction to neo-colonial conditions, among other causes related to tribal and

religious differences. If we were to sum up, the Western analysts conclude that

the fault for the absence of development in Africa rests squarely with internal

dynamics and has absolutely nothing to do with Western imperialism as a chronic

presence.

When we examine the lofty promises of growth and

development by the UN, World Bank and Western governments whose only interest

is to assist corporate control of Africa’s resources and market share the

result is that by 1995, 25 per cent of the people in the sub-Sahara region had

no job and were homeless. Even more alarming, Africa’s agricultural growth

rates have been declining since 1965. From an annual average of 2.2 per cent

(1965-1973), to 0.6 per cent (1981-85), per capita food production continued to

decline throughout the 1980s and 1990s, necessitating four times as much food

aid. Why is anyone surprised that there is the level of rebel activity,

including jihadist as of late, when the question really ought to be why is

there not more such activity given these conditions that people in the West

would not tolerate and demand change?

There are those who argue that China’s presence

actually helps to tame the sociopolitical mood throughout the continent. China

is investing in everything - hydro-power, dams, water and sanitation, ports,

railroads, roads, mining, timber, fisheries and agriculture. At the same time,

France and the rest of Europe as well as the US and the rich Arab countries

have been competing with China and want to maintain their market share. What

exactly this entails for the people of Africa and the development model that

would eventually lift the majority of the people from abject poverty is another

story.

The Chinese are not in Africa to lift living standards

for the population but to strengthen their global competitive position. China

will need Africa’s raw materials, everything from foodstuffs to minerals, in

order to remain a global economic power in the 21st century. China accounts for

about one-fifth of the planet’s population, but it only has six percent of the

planet’s water and nine percent arable land, forcing its government to look

outside its borders to sustain its growth and development. Just as Africa

provided cheap raw materials and cheap labor for Europe and the US from the era

of colonialism until the rise of China as a global economic power, in the 21st

century it will play a similar role with China competing for Africa’s cheap raw

materials and labor. Investment has risen from a mere $210 million in 2000 to

$3.17 billion 2011 and it is expected to skyrocket.

Africa is the world’s fastest growing continent for foreign

direct investment (FDI), but it starts out at such low levels that it can only

go higher. While historically FDI went primarily to the extractive industries,

there is new emphasis on manufacturing, with energy as a key industry where

revolutionary methods could make a difference in bringing electricity to more

people than ever and make manufacturing even cheaper. The continent’s global

share of FDI rose from around 3 per cent in 2007 to 5 per cent in 2012, a

period of global recession. But among the top 25 countries in the world with

the highest incoming FDI, Africa is nowhere to be found; and if it were not for

South Africa, the continent as a whole would be at the very bottom along with

some of the Eurasian countries. As miraculous as it may appear, China’s share

of overseas direct investment in Africa is a mere $26 billion, while France and

UK continue to lead in this category. On the other hand, few would argue that

China is poised to impose economic hegemony of some type over Africa under an

integration model presumably better than what the French and the British had

imposed after decolonization.

By extending concessional loans – more generous terms

and longer term – to the tune of $10 billion amid the global recession of 2009

to 2012, China bought itself enormous influence without literally dictating

terms down to the minute detail as do the IMF and World Bank. Chinese President

Xi Jinping doubled the concessional loan commitment to Africa from $10 billion

to $20 billion in the 2013-2015 period, and the Chinese Export-Import Bank

announced an ambitious financing program of $1 trillion by 2025; something that

could be scaled back owing to the slowing Chinese economy in 2015.

Although Africa accounts for such a small percentage

of Chinese global investment, Africa has been a top foreign aid recipient. Aid

donors have always used it as a policy instrument and leverage in every respect

to influence not only investment and trade policy of the aid recipient but

defense and foreign policy as well. In providing various types of aid to

Africa, from medical and humanitarian to debt relief and development, China is

in fact investing in good will diplomatically as well as economically for the

future market share that it wants in Africa.

Can we expect from China what we have seen on the part

of the European and US companies in Africa since the 1960s? From the early

1960s to the present, large foreign companies secure public financing for

privately operated projects that have been uneconomic across Africa. However,

the foreign firms risk no capital of their own because their loans to finance

their operation are guaranteed by their governments or development banks, as

are interest and profits. Because most of the investment is invariably in

mining and commercial agriculture, involving multinational companies like

Monsanto, the Carlyle Group, Shell, and other Wall Street and EU giants, the

goal is to strengthen the export sector by taking advantage of cheap labor

without much benefit for the broader economic diversification in a continent

desperate for greater self-sufficiency.

Although China has followed this pattern, its focus on

developing the infrastructure in a number of African countries has the

potential of laying the foundations for a sustainable diversified inward

oriented economy. After all, China has provided assistance for schools and some

textile factories, but it often labels loans as “aid”, and most of its

investments go to those countries rich in natural resources.

Foreign investment in Africa under terms no developed

country would permit is virtually unregulated, thus constituting a drain of

natural resource wealth. Suffering the lowest labor values on the planet,

Africa attracts foreign capital investment because it is the next frontier to

realize high profits. Moreover, foreign capital flows because foreign

businesses demand that African countries provide local financing under

government-guaranteed loans and very generous terms that include profit

repatriation, liberal terms on the environment, and minimal labor protection.

According to the World Bank that has partnered with

China on many projects, the goals in Africa include (i) accelerating

industrialization and manufacturing; (ii) making special economic zones (SEZs)

and industrial parks work; (iii) infrastructure and trade logistics, including

regional integration; (iv) creating the conditions to accelerate responsible

private sector investment, (v) skills development for competitiveness and job

creation, and vi) improving agricultural productivity and expanding

agribusiness opportunities.

These are indeed lofty goals, and one could argue that

all countries undergoing industrialization had to suffer, so must Africa,

despite its unique relationship with industrialized nations. If we analyze each

of the above points that the World Bank has outlined, we conclude that the goal

in Africa is to create a climate conducive to foreign corporate investment

under the best possible terms. There is nothing about protecting workers’

rights, collective bargaining, livable wages, appropriate affordable housing,

hospitals and schools, and above all under a political regime that respects

human rights and civil rights pursuant to principles of social justice. The

only concern of the investors, governments, and international organizations

assisting them in Africa is the investment itself not the social, cultural,

economic and political welfare of the people.

Part III: The new scramble for Africa, narcotics and

human trafficking

There is a 21st century version of "the scramble

for Africa", a continuation of what started in the 19th century

(1880-1914) by the Europeans who pillaged the continent's resources,

systematically exploited its people, caused community and regional wars,

destroying its culture; and all of it by invoking social Darwinism and other

Eurocentric theories, including ethnocentrism and 'exceptionalism', to justify

white hegemony. The new round of neo-colonial race to carve up Africa's

lucrative agricultural lands, mineral wealth, fishing rights within its

territorial waters also extends to its geographical location that makes it so

convenient for South American cocaine trade through West Africa and

heroin-cannabis trade through East Africa.

According to the World Bank (September 2010), more

than 110 million acres of farmland (the size of California and West Virginia

combined) were sold during the first 11 months of 2009. This was all in a mad

rush of foreign private and government investors to secure cheap land (and

labor to work the land), and all during the most serious economic recession in

the postwar period. Between 1998 and 2008, the World Bank provided $23.7

billion for agribusiness around the world, much of it in Africa promoting what

it calls 'efficient and sustainable' agriculture. Along with the erosion of

subsistence farming that sustained families, there is the corresponding erosion

of subsistence fishing owing to competition from European and Asian commercial

fishing operations in coastal Africa. All of this is an integral part of the

corporate control of Africa with the support of governments in the advanced

capitalist countries and with the backing of the IMF and World Bank Group’s

subsidiary agencies like the International Finance Corporation (IFC).

In 2010 the IFC invested an estimated $100 million in

agribusiness in sub-Saharan Africa, compared with merely $18 million per year

in the previous decade. Naturally, IFC and World Bank investments which run

into the billions focuse solely on corporate agriculture that displaces the

small farmer. This despite the advice from experts in sub-Saharan countries who

argued that the best use of farmland is to distribute it to villagers (about 12

hectares per family) and give them the means to cultivate it to end hunger

while also generating a potential surplus for trade. Foreign-owned agribusiness

backed by their governments and international financial organizations such as

the IFC produce commercial crops for export, while the native population

remains poverty-stricken. It should be noted that foreign aid for Africa's

agriculture dropped by 75 per cent since 1980, thus creating the need for

private foreign investment in the sector. This is all in the name of furthering

the goals of privatization that Western neo-liberals push across the world with

devastating consequences for workers and peasants.

In the last one hundred years, agriculture in the

industrialized countries has undergone a revolution that has resulted in just a

small segment of the labor force earning its living from farming, animal

husbandry and fishing. Technology and science applied to the sector has raised

production and made agriculture less labor intensive just as specialization and

concentration has resulted in higher productivity. Modernization of the primary

sector of production entails that large commercial operations in the primary

sector of production, backed by favorable government policies, have taken over

the sector that requires expensive agrochemicals and machinery, and a

distribution network to secure steady profits. In Africa’s case, only large

invariably foreign-owned commercial enterprises are able to operate under this

model of development, forcing the small farmers and peasants into poverty.

With each recessionary cycle more small farmers in

Africa and around the world are squeezed out of business, while neo-liberal

apologists not just in the corporate boardrooms and the media, but in

government and UN continue to sing the praises of large scale commercial

operations as the panacea for capitalism. The transition from subsistence to

commercial agriculture first in Western Europe and then in US freed the surplus

labor force for the manufacturing and service sectors of production. In the

case of Africa, however, there is no manufacturing or service sector large

enough to absorb the surplus labor force that is uprooted from subsistence

farming and animal husbandry.

The assumption by governments, banks, and mainstream

economists is that commercial agriculture in the form of agribusiness is a

necessary development of modernization. Another assumption is that only

large-scale agribusiness, which is subsidized by government and international

organizations like the World Bank and IFFC among others, can meet the world's

rising food demand while keeping costs low. After all, manufacturing is just

around the corner for Africa, although it promises to be the kind of

manufacturing we have seen in Bangladesh and other south Asian countries, where

living standards are very low and working conditions very poor.

Given the trend toward corporate agriculture, in the

last fifteen years, governments and private firms from around the world have

been investing in sub-Saharan Africa because corporations chase the highest

return for the lowest possible investment under the most favorable conditions

to capital possible. Besides agribusinesses acquiring more land, banks, hedge

and pension funds, commodity traders, foundations and individual investors have

been buying land as part of portfolio investments for an average of $1 per

hectare. This is in an attempt to cash in on low-cost land and labor amid a

growing demand for raw food products and bio-fuels.

The EU is hoping to reduce carbon emissions by using

at least 10 per cent bio-fuel of all fuel products by 2020. The US is aiming to

reduce its foreign dependence on oil by 70 per cent in the next 15 years. With

the help of the World Bank and IFC, the EU and the US have been looking to

Africa - more than 700 million hectares appropriated for agribusiness - as the

continent to invest in bio-fuels; this at a time that the Europeans have also

been eyeing Africa as the next frontier for solar energy. Latin America is also

a target for bio-fuel and other agrarian investment, but Africa offers even

more attractive prospects in part because of the Arab and Chinese interest as

well.

In the past decade, India, China, Japan, and Arab

countries have joined the 21st century scramble for Africa, in some cases

because governments are concerned about soil, water, and natural resources

conservation in their own countries. Private investors and governments are

aggressively seeking to partition Africa's rich agricultural land as the cost

of agricultural commodities is expected to rise once the current recession

ends. Saudi Arabia has set aside $5 billion in low-interest loans to Saudi

agribusinesses to invest in agriculturally attractive countries. Another reason

for the new scramble for Africa is because of what the UN Food and Agricultural

Organization calls 'spare land', areas not under cultivation, or underutilized.

Developed countries have used Africa for its raw

materials and as a consumer of imported manufactured products and foreign

business services, but not as roughly equal trading partners as is France and

Germany. Rather, Africa has been the victim of unequal terms of trade, and

external control of its key extractive sectors. In short, Africa remains

semi-colonial and continues to become increasingly dependent on developed

countries for overvalued manufactured products and services while exporting raw

materials at prices commodities markets in the West determine based on

speculative interest.

One is favorably impressed by the rhetoric regarding

“sustainable development” that the media, governments, the World Bank and even

corporations promise as though such development translates into social justice.

After all, the hypocrisy of corporate responsibility regarding the eco-system

has been exposed repeatedly not just by oil companies operating in Nigeria, but

even by Volkswagen as its flagrant scandal regarding emissions manipulation

proved in October 2015. The EU and US quest for bio-fuel development in Africa,

and for that matter in Latin America, has nothing to do with 'sustainable

development' or engendering greater 'self-sufficiency' or helping to 'develop'

Africa - rhetoric that the UN, World Bank, western governments and

multinational corporations are using to make 'the new scramble for Africa' more

palatable to the world. The rhetoric is obligatory to placate the masses to

retain their trust in the corporate world.

Will the people of Africa solve the chronic problems

of poverty and disease as a result of the exploitation of land and labor to

satisfy the demand for food and bio-fuels in Western nations? Africa's food

requirements will double in the next two to three decades, a point that foreign

agribusinesses, governments and IFC and World Bank are using to justify the

commercialization of agriculture under foreign ownership. In the process of the

neo-colonial land-grab, evictions of peasants and small farmers, entire

villages uprooted, civil unrest, and citizens' complaints of 'land grabbing'

have been common. Protests owing to social injustice do not stop governments

from approving agribusiness deals backed by powerful forces. One common

justification used for the new scramble for Africa is that the acquired

territories are not utilized or 'wasteland'. Governments often do not charge

agribusiness for the water they use. Just a single agribusiness belonging to an

Arab investor in Ethiopia, for example, uses as much water as 100,000 people -

water of course is the most precious commodity in many parts of Africa. This is

the reality of agribusiness and its role in drought-ridden East Africa.

One reason for the rise of the informal economy that

includes everything from hand-carved wood statues to cocaine from Colombia and

heroin from Afghanistan using West and East Africa as hubs before sending the

product to Europe is that the neo-liberal model of development has failed. In

fact, it has failed so miserably that young impoverished Africans join rebel

groups inspired by radical Islam or community loyalty. At the same time the

combination of rebel activity, and violence linked to narcotics as well as

human trafficking and weapons, also linked to radical Islam and tribal

allegiances in some cases, is a reflection of a neo-colonial system, no matter

the lofty claims by Western governments, NGOs, media, the UN and World Bank

that they are looking after the interests of African people.

Narcotics trade in Africa

Africa's structural problems have contributed to a

thriving narcotics trade through the Western and Eastern areas because of

geographical considerations. Given that in sub-Saharan countries the percentage

of labor force involved in agriculture, animal husbandry and fisheries ranges

from 50 to 75, the result of agribusiness is to create a larger percentage of

wage laborers instead of engaged in the subsistence economy. A percentage of

this population will choose to make a living in illegal activities – human

trafficking, weapons, and narcotics trade; others in piracy, still others in

the thriving teenage prostitution business that has a ready market around the

world.

All of this is an integral part of an informal economy

that according to the African Development Bank contributes 55 per cent of GDP in the sub-Sahara region and

accounts for 80 per cent of the labor force. “Nine in 10 rural and urban

workers have informal jobs in Africa and most employees are women and youth.

The prominence of the informal sector in most African economies stems from the

opportunities it offers to the most vulnerable populations such as the poorest,

women and youth.”

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime has been warning for

many years that a number of West and East African countries are now immersed in

the international drug trade, a reality that has consequences for criminal

activity and the overall subterranean economy and politics of Africa. Because

the drug trade is so lucrative, the income it generates is often larger than

the entire GDP of some African countries. This is the case with Guinea-Bissau

where the cocaine trade amounts to more than $2 billion and where violent crime

in this former Portuguese colony has been rising steadily. The situation is not

very different in Senegal where the airport at Dakar has been used to transport

cocaine from Latin America to Europe.

While West Africa is a hub for cocaine from Colombia

and Peru, East Africa is a hub for heroin and cannabis coming to the region

from South-East and Southwest Asia by air and sea, often onboard vessels that

transport legitimate commodities, and often owned and operated by European shipping

tycoons and of course European banks to launder drug money. A number of Greek

shipping tycoons have been linked to the illegal narcotics trade in Africa, but

they invariably enjoy European connections for distribution and laundering of

enormous amounts of money considering the street value is 20 times higher than

its original value when the products land in Africa.

While the drug trade may appear that it is outside the

mainstream of economic activity, it actually operates under the same laws of

capitalism and in practice under similar routines. The laws of supply and

demand apply as does the cooperation of government, albeit at a sub-level of

illegality through bribery no different from when a multinational corporation

bribes officials. Moreover, just as the extractive industries drain Africa of

capital so does the narcotics trade. People involved in this business are in

fact businessmen running operations of an illegal product but observing all

other rules of the market within which they operate and which makes no

distinction between drug money and corporate money. The bottom line for Africa

is that both the corporate and drug businesses result in taking capital out of

the area and leaving behind all the social and political problems.

The process of de-capitalization, especially amid

recessionary cycles in the world economy as in the current case of depressed

commodity prices, only increases the problems with the informal economy that is

a mere extension of the overall outward-oriented dependent economy and a

colonial remnant that gives rise to illegal activities. East Africa around the

Gulf of Aden is already the pirate center of the world, and this in addition to

the weapons and human trafficking trade. Everything from illegal handicraft

items to diamonds and gold are illegally traded. West Africa is slowly

transforming itself into the new world center for South American

narco-traffickers. Guinea, Mauritania, Guinea Bissau, Ghana, Benin, Sierra

Leone, and Senegal are among the most significant intermediary narco-traffic

countries linked to the Colombia-Venezuela coca trade.

In the absence of official cooperation, everyone from

custom officials, port authority, police, army and navy, all the way up to

cabinet officials, the drug trade would not be possible. In short, the drug

trade in Africa is an integral part of the political system and informal

economy that enjoys protection from a wide variety of players. This makes

transport low-risk in comparison with the Caribbean. With Russia as a new

player in the international drug trade and oligarchs behind the regime, the

activity has increased in the last decade.

During the "just say No!" campaign of the

Reagan era the US had the highest per capita use--US population was around 4

per cent but consumed 25 to 40 per cent of the world's illegal drugs--and this

is not to say that a legal pill-for-everything panacea in the US is not at its

root a cultural trait. Today, however, both UK and Spain surpass the US in per

capita use of cocaine, and both countries along with Portugal and France are

the major destinations for coca that comes from Latin America through West

Africa.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that Somalia, currently in

the process of establishing a central authority, is host to widespread illegal

transactions, including drug and arms trafficking. There are two important

international airports in the region, servicing the capitals of Ethiopia and

Kenya, which are used as transit points for drugs. Both airports have

connections between West Africa and the heroin producing countries in South

West and South East Asia. There is also an increasing use of postal and courier

services for cocaine, heroin and hashish.

Heroin trafficking from Pakistan, Thailand and India

to East Africa has been rising in the last two decades. Some of this heroin

finds its way to West Africa that also exports to Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya

through Ethiopia. Increasing numbers of Tanzanians and Mozambicans are involved

in the trafficking of heroin from Pakistan and Iran, given the limited options

in the formal economy. West African and East African drug syndicates are

inter-connected as they are to smugglers from Latin America and South Asia,

reflecting high level of organization.

Considering that multinational corporations from Shell

Oil to Siemens have a long history of bribing African officials as they do

non-Africans, narcotics traffickers' mode of operation is no different than

that of "legitimate" businesses. And if the opportunity presents

itself to make a living why is "dirty money" any less valuable than

"clean money," the latter of which seems to be less than $500 a year

for most Africans? Judging on the basis of postwar recessions when per capita

income has dropped as much as 50 per cent, this means that in this current

crisis Africa will not only suffer greater impoverishment than the rest of the

world, but its economic problems will cause more ethnic and community conflict,

more epidemics, more intra- and inter-continental emigration, and more

political turmoil than any developed nation can expect.

Such a climate is ideal for more piracy, more weapons

and narcotics transfer, more human trafficking, and all of it part of the

colonial and neo-colonial legacy of outward oriented economy benefiting the

developed countries. Though the continent is in need of debt-relief and

development assistance for the short-term, the solution for a small segment of

unemployed and destitute young Africans is drugs, guns, and human trafficking

that generates money, although most of that money does not stay in the region

and creates violence that disrupts legitimate economic activity.

Conclusions

The social fabric disrupted yet again by 'the new

scramble for Africa', continued political instability is a guarantee as much as

a rise in crime and social unrest. Amazingly, the same institutions that

contribute to Africa's devastation claim that they are acting in the name of

progress, sustainable development and efficiency, helping to raise productivity

and exports, to create jobs by bringing foreign investment,' etc.; the modern

versions of "The Whiteman's burden".

The 'politically palatable' rhetoric of 'efficiency

and sustainability' has resulted in an outward-oriented agrarian sector

catering to foreign markets instead of inward-oriented economy designed to meet

the rapidly rising population's food needs. In 16th century England, farmers

switched to animal husbandry owing to rising demand for wool textiles. Peasants

starved as the cost of grain increased, thus "sheep ate people". In

this century, 'agribusinesses will be eating Africans'.

Apologists of agribusiness justify their support by

various arguments including ‘no country has developed’ with two-thirds of its

labor force living off the land and dependent on extractive industries. It is

an interesting coincidence that just as sub-Sahara Africa has been targeted by

drug lords in the last few years, it is also targeted by corporate farm

investors whose mode of operation is to use the low-valued land and labor and

corrupt public officials in order to serve foreign market demands. Rural

poverty will rise as a result of foreign corporate investment in African

agriculture. Will the 'new scramble for Africa' by corporate investors and drug

lords result in the elimination of famine and disease; will it result in higher

rising living standards for the native population, or will it be another form

of neo-colonialism in the name of progress?

Using the pretext of “terrorism”, a guerrilla movement

under the flag of jihadists in recent years, the West and pro-West regimes

default all problems on such fanatics in Nigeria, Chad, Sudan, Somalia, Kenya,

Niger, Cameroon, Mali, Uganda and Mauritania. In other words, the US and its

European partners would have the public believe that for decades when there

were no Islamic jihadists, sub-Sahara Africa under colonial and neo-colonial

rule enjoyed social justice and upward social mobility under democratic

regimes. Even more insulting is the implication that the Islamic militants are

the cause and not the symptom of Western exploitation of Africa and that if

they are eliminated the continent would have no problems. As counterproductive

as jihadist warfare has been, and as futile in achieving its goals, it is not

the cause but one more symptom of the neo-imperialist structure in the

continent from Libya to South Africa, from Nigeria to Kenya.

Besides defaulting Africa’s problems on Islamic

‘terrorism’, there are also the advocates of the neo-Malthusian theory - too

many people too few resources, rather than unequal income distribution. It is

true that drought is a cyclical natural disaster in parts of Eastern and

Southern Africa and generally a problem in a few other parts as well. However,

does drought justify Malthusianism and does it explain structural impediments

to African development? This is not say that a form of managed population

control is not desirable, but this is a matter of resources and education for

the general population.

Uniting and organizing at the grassroots to end racist

neo-colonial exploitation whether in the form of the formal economy based on

mineral and agricultural exports or in the informal economy that includes

narcotics is the only solution for Africans. Working toward sustainable

development can only come from indigenous movements that first change the

externally-dependent political regimes and then undertake to change the social

order that would engender economic growth under an inward-oriented model. Given

the deep historical ethnic antagonisms in Africa for which westerners are

partly to blame, and the even stronger western neo-colonial foundation the

prospects of any of this taking place in the forthcoming decades is highly

unlikely. Africa will remain the continent of contradictions with the world's

poorest people, but some of the world's richest natural resources.

* Jon V. Kofas, Ph.D., retired professor of

history, is author of ten academic books and two dozens scholarly articles.

Specializing in international political economy, Kofas has taught

courses and written on US diplomatic history, and the roles of the World Bank

and IMF in the world.

Source:

Pambazuka

Open Letter to UN

Ambassador Nikki Haley

|

| Nikki Harley |

By Richard Falk and Virginia Tilley

Dear Madam Ambassador:

We were deeply disappointed by your response to our

report, Israeli Practices Toward the Palestinian People and the Question

of Apartheid, and particularly your dismissal of it as “anti-Israeli

propaganda” within hours of its release.

The UN Economic and Social Commission for West Asia

(ESCWA) invited us to undertake a fully researched scholarly study. Its

principal purpose was to ascertain whether Israeli policies and practices

imposed on the Palestinian people fall within the scope of the

international-law definition of apartheid. We did our best to conduct the study

with the care and rigor that is morally incumbent in such an important

undertaking, and of course we welcome constructive criticism of the report’s

method or analysis (which we also sought from several eminent scholars before

its release). So far we have not received any information identifying the flaws

you have found in the report or how it may have failed to comply with scholarly

standards of rigor.

Instead, you have felt free to castigate the UN for

commissioning the report and us for authoring it. You have launched defamatory

attacks on all involved, designed to discredit and malign the messengers rather

than clarify your criticisms of the message. Ad hominem attacks are usually the

tactics of those so seized with political fervor as to abhor rational

discussion. We suppose that you would not normally wish to give this impression

of yourself and your staff, or to represent US diplomacy in such a light to the

world. Yet your statements about our study, as reported in the media, certainly

give this impression.

We were especially troubled by the extraordinary pressure

your office exerted on the UN secretary general, AntónioGuterres, apparently

inducing him first to order the report’s removal from the ESCWA website and

then to accept the resignation of ESCWA’s distinguished and highly respected

executive secretary, Rima Khalaf, which she submitted on principle rather than

repudiate a report that she believed fulfilled scholarly standards, upheld the

principles of the United Nations Charter and international law, and produced

findings and recommendations vital for UN proceedings.

Instead of using this global forum to call for the

critical debate about the report, you used the weight of your office to quash

it. These strident denunciations convey a strong appearance of upholding an

uncritical posture by the US government toward Israel, automatically and